Chika Mara (Graffiti)

From Stage to Street: Artistic Movements in Bangladeshi Social Commentary

June 2, 2025

“Subodh, are you alive?”

June 2, 2025Lexicographically speaking, graffiti came from the word ‘Graffein’ which refers to ‘scratch’. So, graffiti is theoretically ‘a scribble on a wall’. Though to be a proper graffiti, it has to be more than just a meaningful scratch. It is meant to be a mirror, a portal, a gateway from this disciplined needy greedy world to the outlaw, the outcast. Not just an art or a slogan on a wall, but a reflection of the true naked state of society. Social commentary of Bengali or Bangladeshi is overwhelmingly expressed via writing mediums like poetry and novels.

The Graffiti or Chika Mara (in Bangla) is often overlooked. It might be surprising that the history of Bangladeshi’s Chika Mara goes back to 1952 when the sapling of Bangladeshi nationalism was sown. (Side lining graffiti under British rule to emphasize the Bangladeshi part.) Believe it or not, the duality of the word ‘chika’ helped its artists to survive under Pakistani rule! Imagine midnight of Amavasya (new moon), three people in front of a wall. One shining a hurricane light, one carrying the paint and one stroking the first letter আ. “Kon he? (Who’s there?)” yelled a Pakistani police as another rasping voice followed from behind, “Idhar kya chal raha he? (What are you guys doing?)”

Modern Bengali are coward enough to run, but oppression forces the oppressed to grow like a dandelion growing through a concrete crack. So, one blatantly replied, “Chika mari…” The police officer held his nose at the disgusting smell that surrounded him and said, “Bohut khub.” (Very good!)”

Confused? Well… Chika also refers to small rats instead of painting and mari can also mean killing. The wall paints had a weird smell making the officers think; that these three youths were killing mice at midnight! Welp, they did ‘chika mari’ the rest of the night as they simultaneously laughed at the incident. Next morning, the wall shone the charcoal aura, “আইয়ুব-মোনায়েম দুই ভাই/এক দড়ি তে ফাঁসি চাই, ২২ পরিবারের বিরুদ্ধে রুখে দাঁড়াও, তোমার আমার ঠিকানা পদ্মা মে ঘনা যমনুা।”.

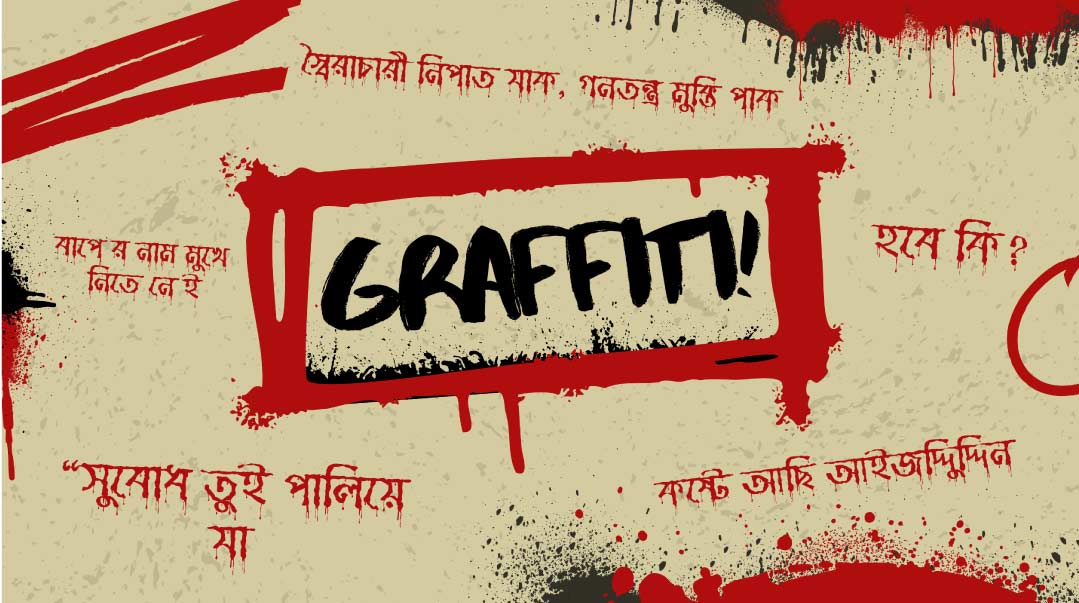

Throughout our East Pakistan history, under the leadership of Ronobi (Rafiqun Nabi) and others, graffiti was a major reflector of the proletaria’s nationalism alongside other artistry mediums. A vivid example of this artistic expression is Noor Hussain, who turned himself into art by writing, “স্বৈরাচারী নিপাত যাক, গনতন্ত্র মুক্তি পাক. (Down with autocracy, Let democracy be free.)” on his body.Now, I will not argue whether his art was graffiti or not; as a wall doesn’t have to be a bricked wall, it can be anything sturdy enough to hold and reflect the feelings of millions. But Nur Hossain showed how this practice of artistic expression has enabled us to slap the oppressor’s face in innovative ways!

Revolution is in our blood, so we accepted a rebel poet as our national poet. However, today the expression of these is just confined to a Facebook post of appreciation or within a yearly program on the poet’s death anniversary. It took me ages to find the writings of those old graffiti, let alone a picture. Which thoroughly reflects how the expression of our true sense of freedom faded away slowly. We devolved into early British colonial Bengali whose life was to just eat, breed and die. The few that still dream, dream of running away from this discrepancy.

Though nobody speaks of this inherent oppression, as our mouths are not allowed to spill the name of our societal father (বাপে র নাম মখেুখে নি তে নে ই). Under all this suppression, came Aizuddin. He drew all over the walls of 90s Dhaka that, “Aizuddin is in pain. (কষ্টে আছি আইজদ্দিুদ্দিন)” Who is Aizuddin? Asked a passer-by as he or she was walking past.

Soon the question turns to why he is in pain. What is his pain? Soon the invisible gap of answers becomes filled with personal narcissism. He is in pain just like me. He wants freedom of speech, just as I do. Not only that, but he wants to scream out loud about the corrupt just like me. That’s why Aizuddin and I are in pain. Aizuddin is me. We hold our breath as we breathe out the above in a sigh, and move on with our monotonous suppressed lifestyle. That philosophical pause is worth a million!

Bangladesh’s Graffiti culture up until Aizuddin was pretty straightforward. It consisted of a rhyming sentence, asking for a demand, and maybe a picture to visualize the need. But Aizuddin was possibly the first Graffiti that made us think from our own perspective. The artist lets the audience speak through the art.

For the rest of the millennia, the last resort of Graffiti will lie in the hands of the fine arts students of renowned Universities. Ranging from “Where is Michael Chakma?” and “To Gaza from Dhaka” to ‘Gang name Graffiti’ and ‘Two Rabindranath in censored position’; we can see the spectrum of Bangladeshi mindset on the walls of the University. (Personal favourite: A Buddha holding a gun in his head, saying ‘Let me die’) But that’s not all.

Welcome to the last but not the least. Summer, 2017. Near the National Metrology Department. A vague black portrait of a bearded scared man running with a caged sun. Text: Subodh, run, time is not on your side. Subodh was seen again near Mirpur 7 and 12 or at Dhanmondi. Sometimes he is sitting holding the sun as his eyes look behind us. Saying, “Subodh, run. People have forgotten to love.”Once he was seen sitting down with his caged sun; putting a hand over the shoulder of a girl next to him. As the text asks, “Subodh, when will it be dawn?”

Sometimes his caged sun was seen to hang on a rope. But always, there was a question at the corner in red bright ink, “Hobeki? (Will it happen?)” Take your time, go on the internet, and give Subodh a stare. Just look at the mighty and ask yourself, “Hobeki?” in your own philosophical view.

Author: Raiyan Tausifur Rahman