An Open Letter to Bangladesh’s Education System and the Way Forward

An Open Letter to the Drowning System in Bangladesh

August 25, 2025“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”- Nelson Mandela But what if the system promoted to empower ends up restrictingminds instead?

A student at a government college in Rajshahi who was brilliant at math, Akashcoulddo math tasks more quickly than anyone else in his class. He topped every boardexam. But when he went on job interviews, he found he couldn’t articulate his ideas well or solve practical problems. He wasn’t alone. Moumita, who was studying science in Jashore, loved biology, and wanted to be a researcher. But her school did not have a real lab, and her ability to get on the internet was limited to an old cell phone with a spotty signal. Then there’s Chaity, a young woman fromDhakawho adored film making. She never had an outlet for her passion in the test-focusedsystem.

These are not isolated stories. They are a symptom – of students who are smart, curious and dutiful, but who are acting out because the game feels even crazier thanusual at this moment, when the transmissions have been hijacked by the simultaneous plagues of a pandemic and racial strife. Schools have spread into even the most distant parts of the country, and more girls are attending classes than ever before. But the system remains locked in time.

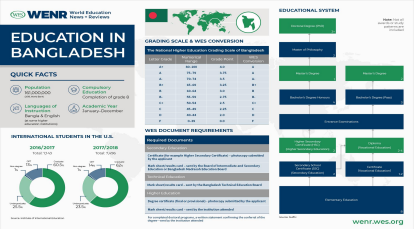

According to a report by CAMPE (2021), almost 70% of Bangladeshi students thinkthat their exams are for memorization rather than understanding. Fromthe PrimaryEducation Completion Exam (PECE) to HSC and university admission tests, we onlyhave to memorize the textbook definition –not use it.

This introduces a dangerous end result – students know what to write in the examination, but they fail to apply what they have learn to real life situations. Employers notice this too. Bangladesh: More than half of university graduates ‘underemployed’ – World Bank ‘Report’. It’s not that they lack ability, or are lazy, or unwilling to learn or be retrained; it’s that the system failed to equip them with the skills necessary to adapt to today’s labor market. Another concern is deep inequality in educational resource availability.

According to a 2022 BANBEIS report, only 29% of the rural schools have established functional science labs, and even fewer are equipped with internet facilities. At the same time, private schools in the cities are teaching coding and robotics, dispatching teams to compete in debate championships. This digital and resource gap is only going to exacerbate if not addressed soon, compromising the idea of equal opportunity.

What about creativity? According to the British Council’s survey 2020, only 10%of students in Bangladesh felt that they were inspired to think creatively in school. They neglect arts, music, theater, sports – which we too often consider “extra” or even“ distractions.” Students like Chaity, who aspires to tell stories on film or by illustration, often hear they should “focus on real subjects.” But in a creative economy, all of those distractions could well end up translating into powerful careers.

all standard but an education in critical thinking, digital literacy, emotional intelligence, and communication skills. Nations like Finland and Singapore routinely use these to great success and consistently have some of the top-performing students in the world (World Bank, 2023).

Second, teachers must be empowered. They serve as the intermediary between policy and students. National educational training needs to center around student-centered teaching, mental health and technology. The right kind of teacher is empowered to foster questions, rather than smother them, and they create innovators, not imitators.

Third, resources should be allocated fairly. Students everywhere in Bangladesh- Dhaka or Dinajpur -should have access to operating labs, computers, libraries andextracurricular experiences. Infrastructure shouldn’t define potential.

Fourth, we must rethink assessments. Exams should be diversified – project work, presentations, teamwork exercises and real-life application tasks can be mixed in with traditional approaches to give a fuller picture of what a student can do.

Lastly, we must empower students to be leaders of change. Student councils, open conversations, feedback loops – these are relatively simple tools that can help make learning more democratic and meaningful. Education isn’t something that is done to someone, it’s something that should be done with someone.

The journey won’t be easy. Reforms require time, patience, and political will. But gradual tweaks can initiate waves. A school in Sylhet that is offering design-thinking workshops. A teacher in Barishal allowing her students to explore documentaries. A university in Dhaka initiating national-level adult creative writing competitions: That is all that all it takes for fission; and that is enough to spark up the entire system. We raise the question once again: Should we be conditioning future generations to only pass tests rather than pass through life with purpose and confidence? Education’s real aim is not to stuff minds with facts, but to open them to questions. To support students not just in remembering, but in imagining. Not to compete, but to collaborate. Not simply in order to survive, but to prosper.

Let’s end the race to the top in education and replace it with a scramble toward meaning. It is this generation that will determine the future of Bangladesh based on how well we teach them to think, dream and lead.

References:

Ahmed, M. (2020). Rethinking Education in Bangladesh. Dhaka Tribune. British Council. (2020). Teaching for Creativity: Bangladesh Report. BANBEIS. (2022). Bangladesh Education Statistics. Ministry of Education. CAMPE. (2021). Annual Education Watch Report. Campaign for Popular Education. World Bank. (2023). Bangladesh Tertiary Education Sector Review. Washington, D.C.

Author: Md. Jonaidul Islam

Position: 6th (WC 2025)

Institution: Bangladesh University Of Professionals (BUP)